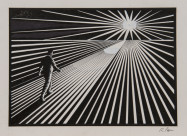

A couple stand on a wharf suspended between water and sky, poised between signs of the eternal and the ephemeral. The ocean is a symbol of a natural force that is vast, ancient and unceasing in the regularity of its action. In contrast, a cloud appears and disappears in an instant. It changes shape and is rather amorphous in substance. Children and daydreamers see pictures in the clouds. In his essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” 1863, poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire argues that art involves an interaction of time-resistant and transitory factors. “Beauty,” writes Baudelaire, “is made up of an eternal, invariable element, whose quantity is excessively difficult to determine, and of a relative, circumstantial element, which will be, if you like, whether severally or all at once, the age, its fashions, its morals, its emotions. Without this second element, which might be described as the amusing, enticing, appetising icing on the divine cake, the first element would be beyond our powers of digestion or appreciation, neither adapted or suitable to human nature. I defy anyone to point to a single scrap of beauty that does not contain these two elements.” Baudelaire was a Parisian who thought of the city as a perfect parade-ground of transitory effects. Robert is more rural in his orientation. He extends Baudelaire’s dichotomy to apply not only to aesthetics, but also to considerations of fate, luck, relationships and happiness in a broader search for meaning.

Cloud