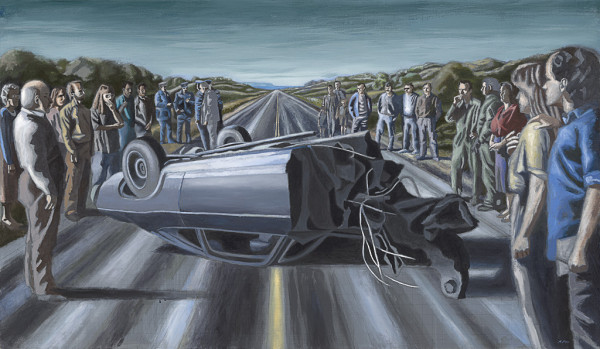

The influence of Andy Warhol is a strong point of departure. Both Warhol and Robert use photos from public sources. In his “Death and Disaster” series (1962-64), featuring car crashes, race riots, and deaths from suicide, electric chairs and atom bombs, Warhol used sensational tabloid images. Robert uses a file photo of a badly damaged car from the Nova Scotia Department of Highways, but surrounds the vehicle with a scene from his imagination. The accident is turned into a ritualized event, attracting a crowd in the open countryside. There is a mixed feeling of curiosity, trauma, wonder.

Warhol’s car crashes question the public consumption of such gory and macabre scenes. Robert’s crowd may exhibit a similar sort of morbid curiosity. However a nascent sense of community seems to be forming as the crowd rallies together. Robert contrasts the symmetry of the landscape and figures with the asymmetry of the mangled car. The victim appears to be the car itself, a mechanical martyr that’s become a monstrosity.

Robert’s title “accident” refers to a sudden reversal of fortune that punctures the order of reality, revealing a much harsher, more unpredictable reality underneath. This reversal of fortune, with its juxtaposition of chaos and order, has a surreal quality. According to André Breton, spokesman for the surrealists in the 1920s: “The greater the sense of distance separating the two realities and the sense of aptness of their coming together, the stronger the image will be, conferring emotional power and poetic realism.” (Willard Bonn, Rise of Surrealism, 2001) Bonn’s history of surrealism goes on to quote the poet Robert Champigny, “who proposed to divide Surrealist images into those that are spatially unlikely, those that are temporally unlikely, those that feature a metamorphosis, and those that depict a monstrosity.” All of these elements are more or less present in Robert’s Accident.